Return Stacking and the Cost of Leverage

Overview

Whenever we borrow money—whether explicitly or implicitly — we should expect to have to pay some sort of financing rate. In this article, we explore this cost of financing in futures contracts, one of the primary instruments used to implement return stacking concepts. We demonstrate that competitive market forces have, historically, kept financing rates in line with overnight borrowing rates (e.g., LIBOR/SOFR) and 3-month Treasury bill rates for Treasury and S&P 500 futures contracts.

Key Topics

Leverage, Financing Rate, Futures, Derivatives, Portable Alpha

The core idea behind return stacking is layering one investment return on top of another, achieving more than $1 of exposure for every $1 invested. This concept is closely related to portable alpha, where investors seek to separate alpha (excess returns) from beta (market returns) to enhance portfolio efficiency.

Of course, if we want to invest more money than we have, it will require us to borrow, which means leverage. One of the key questions with any form of leverage is: how much does it cost? What is the financing rate of the money borrowed?

Many individuals will already be very familiar with this concept. Homeowners with a mortgage have borrowed money to buy an asset at a defined financing rate. Unfortunately, there are no mortgages for investors looking to buy exposure in alternative investment strategies, so we must look elsewhere for our leverage.

In some cases, it is possible for investors to borrow directly from their brokers. For example, Schwab, TD Ameritrade, and Fidelity all offer margin accounts that allow you to borrow money with rates varying from 9.25% to 14.75%, depending upon how much money you plan to borrow (as of the date of publishing, 1-Month Treasury Bill reference rate is 5.51%).

Unfortunately, these interest rates impose an exceptionally high hurdle for any investment we might look to stack, since we will only be able to keep any return in excess of the borrowing rate.

Fortunately, certain markets — such as exchange-traded futures — offer much cheaper rates for borrowing.

The Theory for Competitive Rates in Futures Contracts

A foundational theorem in financial markets is the Law of One Price. This law states that—under certain assumptions—any assets with identical cash flows will have the same price.

With this in mind, consider two scenarios. In the first, we sell short a three-month S&P 500 futures contract. As a reminder, a futures contract will define an asset, a quantity, a date, and a price (among other things). The seller says, “I will deliver you this asset, on this date, in this quantity, and accept this price.” The buyer says, “I will accept delivery of this asset, on this date, in this quantity, and pay you this price.” Importantly, no cash actually changes hands when the contract is struck; it is simply an agreement between two parties. By selling the three-month S&P 500 futures contract, we’re locking in a price, in the future, at which we will deliver shares of the S&P 500.

In the second, we sell short the shares in the S&P 500 and invest the proceeds in three-month U.S. Treasury bills. In three months—at the same expiration date of the futures contract—we will buy back the shares and return them, along with any interest owed from borrowing the shares and any dividends paid along the way.

Note that both strategies require the same initial investment (nothing) and should provide the exact same proceeds. Under the Law of One Price, this means that the price of the futures contract should be determined by the current price of the futures of the second trade: the current level of the S&P 500, the cost of borrowing, and dividends. If the futures price deviates from this relationship, it implies an opportunity for profit.

(More generally, the relationship between futures markets and their underlying is called Spot-Futures Parity.)

In practice, the ability for this relationship to hold will be determined by real-world market frictions, such as transaction costs and the balance sheet constraints of large institutions holding these markets in order. This can increase the real-world cost of borrowing away from the theoretical “risk-free rate.” Nevertheless, in a market where institutions compete to profit from this trade, we would expect the cost of borrowing to be driven towards the risk-free rate.

For assets with physical delivery (e.g., commodities), there are additional costs. For example, if we are the seller, we have to take into account the costs of physically storing the asset, insuring the asset, and delivering the asset. These are collectively known as the “cost of carry.”

One of the big differences with futures, however, is that unlike when you borrow money and have to pay an explicit interest rate, the interest rate (and cost of carry) is ultimately embedded into the return of the futures contract itself. So, while you need to be aware of the financing rate, there are no additional operational steps required to manage the interest.

Register for our Advisor Center

Tools Center:

Easily backtest & explore different return stacking concepts

Model Portfolios:

Return stacked allocations, commentary and guidance designed

for a range of client risk profiles and goals

Future Thinking:

Receive up-to-date insights into the world of return stacking theory and practice

The Empirical Evidence for Futures Financing Rates

Theory is fine, but what costs do we actually find in practice? Here we will look at two different markets: S&P 500 Futures and 10-Year U.S. Treasury futures.

S&P 500 Futures

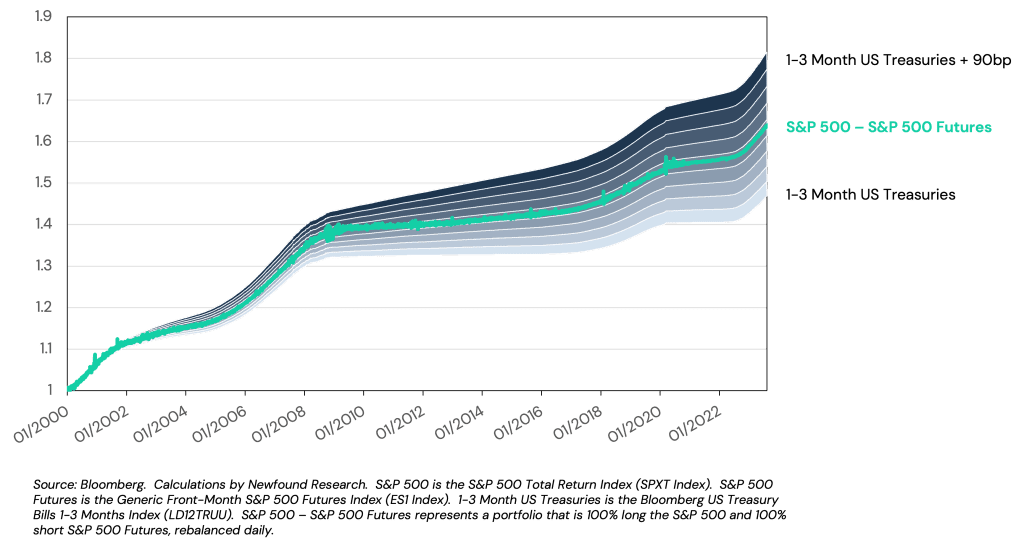

To examine the implied borrowing cost embedded in S&P 500 futures contracts, we construct a portfolio that goes long the S&P 500 and short an S&P 500 futures contract. The idea here is that because the S&P 500 is a fully funded position, whereas the futures contract requires zero funding, the difference in their return should isolate the implicit cost of funding in the S&P 500 futures.

Or, more simply: if we replaced our S&P 500 position with S&P 500 futures, how much would we expect to underperform over time? That underperformance should capture the embedded financing costs of futures.

Figure 1: Measuring the implied cost of financing in S&P 500 futures versus different Treasury Bill benchmarks

Source: Bloomberg. Calculations by Newfound Research. S&P 500 is the S&P 500 Total Return Index (SPXT Index). S&P 500 Futures is the Generic Front-Month S&P 500 Futures Index (ES1 Index). 1-3 Month US Treasuries is the Bloomberg US Treasury Bills 1-3 Months Index (LDZ1TRUU). S&P 500 – S&P 500 Futures represents a portfolio that is 100% long the S&P 500 and 100% short S&P 500 Futures, rebalanced daily.

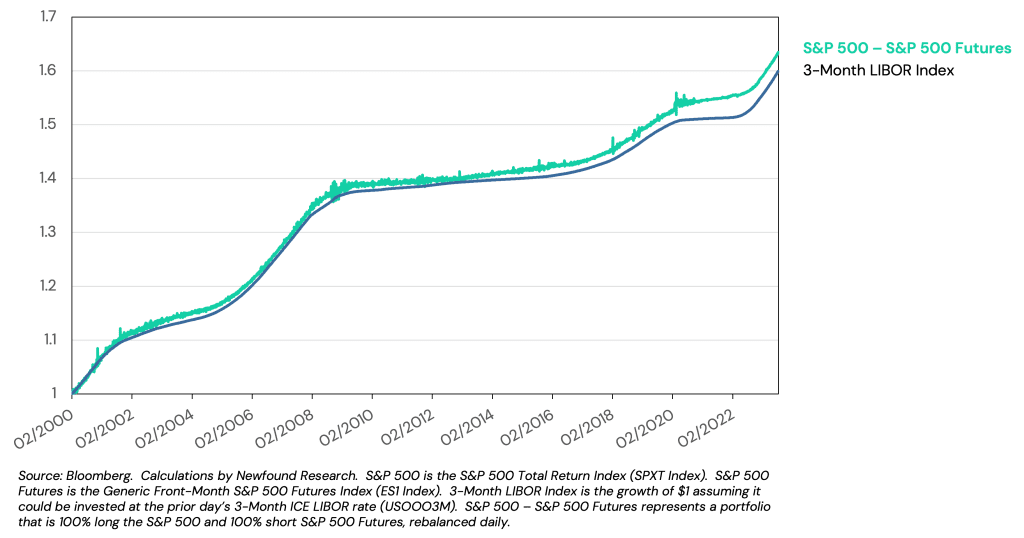

The added spread above Treasury bills reflects the added cost of borrowing for large institutions above the risk-free rate, which will account for frictions such as credit risk. In the figure below, we plot the same trade versus 3-Month LIBOR. While discontinued, we can see that, historically, the rate of financing available to those trading S&P 500 futures approached the cost of borrowing available to some of the largest institutions on Wall Street.

Figure 2: Measuring the implied cost of financing in S&P 500 futures versus 3-month LIBOR/SOFR

Source: Bloomberg. Calculations by Newfound Research. S&P 500 is the S&P 500 Total Return Index (SPXT Index). S&P 500 Futures is the Generic Front-Month S&P 500 Futures Index (ES1 Index). 3-Month LIBOR Index is the growth of $1 assuming it could be invested at the prior day’s 3-month ICE LIBOR rate (US0003M). S&P 500 – S&P 500 Futures represents a portfolio that is 100% long the S&P 500 and 100% short S&P 500 Futures, rebalanced daily.

The Return Stacking landscape is ever evolving, go deeper by connecting with a team member.

10-Year U.S. Treasury Futures

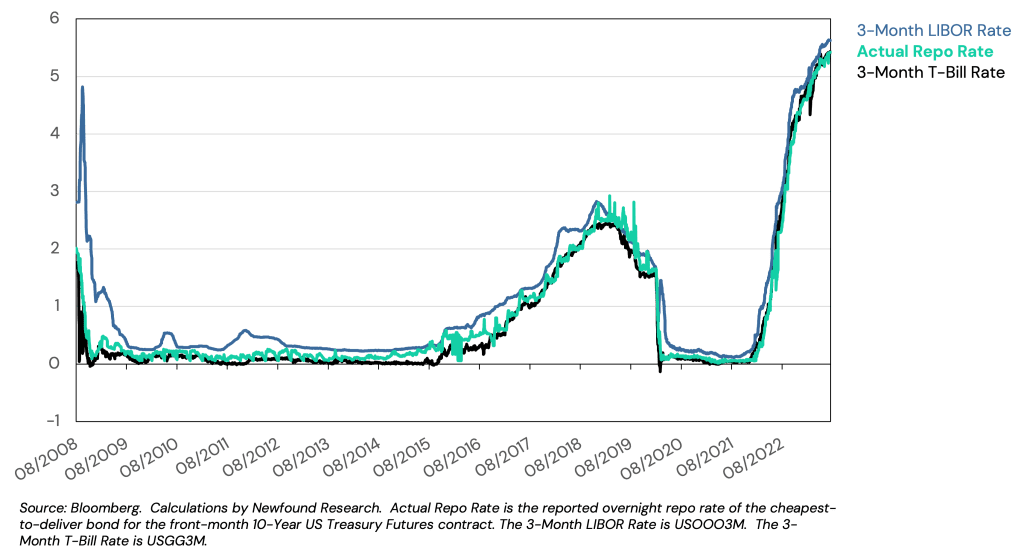

As our second example, we will examine 10-Year U.S. Treasury Futures. With this contract, we can track the actual bond due to be delivered at expiration and its associated repo rate—i.e., the cost of borrowing that bond in the overnight repo market.

As with our original theoretical example with the S&P 500, the cost of borrowing the underlying Treasury bond is an important input to the implied financing available in Treasury futures. In the figure below, we can see that this rate has historically hovered above the 3-Month Treasury Bill rate but below the 3-Month LIBOR rate.

Figure 3: Measuring the implied cost of financing in 10-Year U.S. Treasury futures versus 3-Month Treasury Bill yields and LIBOR

Source: Bloomberg. Calculations by Newfound Research. Actual Repo Rate is the reported overnight repo rate of the cheapest-to-deliver bond for the front-month 10-Year US Treasury Futures contract. The 3-Month LIBOR Rate is US0003M. The 3-Month T-Bill Rate is USGG3M.

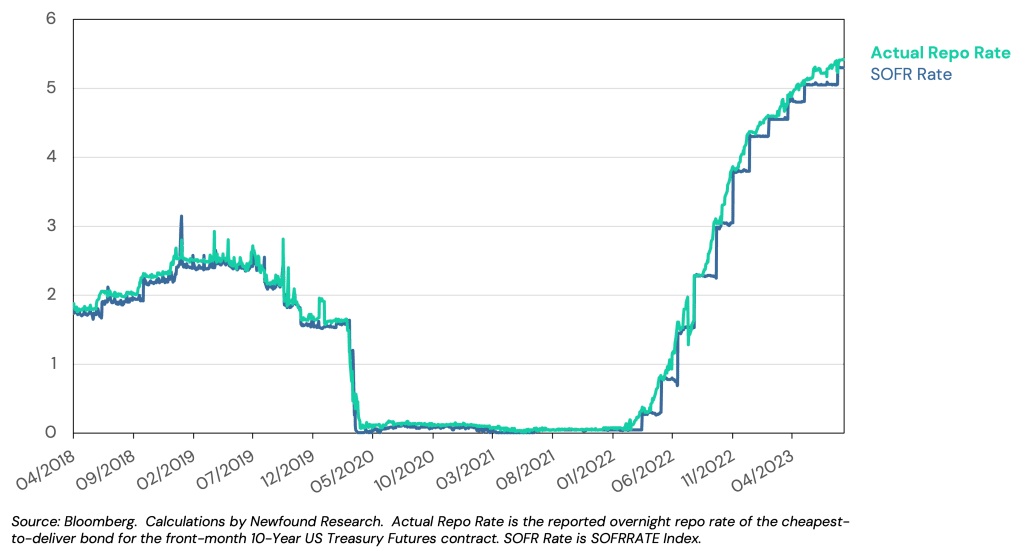

We can also see that this rate has traded closely to SOFR. Again, as with S&P 500 futures, Treasury futures provide an implied financing rate that is competitive with the borrowing rates available only to the largest institutions on Wall Street.

Figure 4: Measuring the implied cost of financing in 10-Year U.S. Treasury futures versus SOFR

Source: Bloomberg. Calculations by Newfound Research. Actual Repo Rate is the reported overnight repo rate of the cheapest-to-deliver bond for the front-month 10-Year US Treasury Futures contract. SOFR Rate is SOFRRATE Index.

Conclusion

As we have seen, the embedded funding rates in both S&P 500 futures and U.S. Treasury futures have historically hovered near three-month U.S. Treasury bill rates and three-month LIBOR (now SOFR) rates. These competitive rates make futures attractive tools for strategies that rely on efficient leverage, such as return stacking and portable alpha. Both approaches depend on efficient leverage to maximize exposure without a proportional capital commitment. Understanding the cost of financing is crucial in ensuring that the benefits of additional exposure outweigh the expenses incurred, potentially enhancing risk-adjusted returns.

To further explore how these concepts can be applied to enhance your investment strategies, read our comprehensive guides on return stacking and Portable Alpha.

If you’d like to learn more about how these techniques can benefit your portfolio, please get in touch with us.