The Risks of Leverage

Overview

For many investors, leverage is a four-letter word. When used appropriately, we believe it is a powerful tool that can enhance returns and improve diversification. In this article, we explore the two primary risks of leverage and how investors can mitigate them.

Key Topics

Leverage, Risk Management, Path Dependency, Diversification

In the realm of investment management, Leverage has a bad reputation. However, underneath the bad press lies a potent tool capable of unlocking many potential benefits. This article delves into the complexities of leverage, dissecting its risks and rewards.

We confront the two primary risks of performance risk and path-dependency risk, unveiling the delicate balance between leverage and uncorrelated assets.

By drawing parallels with the familiar world of mortgages, we demystify complex financial instruments, emphasizing the importance of diversified return potential and robust capital reserves as foundations for performance stability.

Leverage: Not the Four-Letter Word You May Think It Is

In the world of investment management, borrowing money—known as leverage—can be a powerful tool. It has been around since the early days of financial markets and, when used wisely, can be used to increase profit potential. However, it also introduces unique risks. It is important to not only understand these risks but also strategies for mitigating their impact.

Some would argue that leverage’s risky reputation is well deserved. After all, leverage is found lurking at the scene of the crime for just about every major financial catastrophe in history. But rarely is leverage found alone. Rather, it is leverage combined with concentration and illiquidity that often creates the powder keg.

Yet that is not always the case. Prudently applied leverage may actually reduce certain measures of risk. Consider Bridgewater Associates, a well-known investment firm that has faced financial crises since 1975. In 1996, they introduced their flagship “All Weather” strategy (often called “risk parity”), demonstrating how leverage can be used to increase the internal diversification of a portfolio.

This strategy uses careful borrowing to spread investment risk across different types of assets like stocks, bonds, and commodities, with each type of investment expected to perform differently in different economic situations. By using leverage this way, Bridgewater seeks to avoid excessive concentration, increasing the internal diversification of their portfolio and therefore, hopefully, the resiliency of their returns.

As a tool, we believe leverage unlocks two opportunities:

- The Opportunity to Enhance Returns: By introducing additional sources of return, leverage creates the potential for long-term outperformance.

- The Potential to Improve Diversification: By thoughtfully introducing differentiated return streams, investors may gain a diversification advantage with the potential to reduce portfolio volatility and drawdowns.

The First Major Risk of Leverage: Performance Risk

When we talk about the danger of using leverage in an investment portfolio, the first major risk that comes to mind for most investors is performance risk. Performance risk is most easily summarized as the risk of losing more money than you would have had you not introduced leverage.

There are three common situations where this risk becomes apparent:

- Existing Exposures: Increasing existing equity exposure in an already equity-heavy portfolio, for instance, can lead to magnified losses if equities experience a significant decline.

- Highly Correlated Asset Classes: Utilizing leverage to amplify exposure to closely correlated assets, like international equities in a U.S. equity-heavy portfolio, may intensify losses during unfavorable market conditions.

- Uncorrelated Asset Exposure: If leverage is used to add exposure to an uncorrelated asset, there exists a likelihood that the diversifying asset may fall alongside core portfolio holdings. However, this probability decreases as exposure correlations are reduced.

There are two key management techniques with respect to performance risk: selection and sizing. Selection refers to the exposure we are adding to our portfolio. The more correlated it is with existing holdings, the greater the risk of increased losses during adverse markets. Sizing refers to the amount of additional exposure we add to our portfolio. Even if we use leverage to add a diversifying asset, adding too much can just end up with the portfolio being overly concentrated in that diversifier!

While there are contexts where amplifying existing exposures may be prudent, we encourage readers to review our Return Stacking Checklist, outlining the fundamental points for employing sensible leverage.

The key point here is to make wise investment choices and decide how much to invest carefully. Instead of simply increasing existing investment exposures, it’s crucial to think about the bigger picture of your entire investment portfolio. Diversifying your investments thoughtfully should be the main goal.

Register for our Advisor Center

Tools Center:

Easily backtest & explore different return stacking concepts

Model Portfolios:

Return stacked allocations, commentary and guidance designed

for a range of client risk profiles and goals

Future Thinking:

Receive up-to-date insights into the world of return stacking theory and practice

The Second Major Risk of Leverage: Path-Dependency Risk

The more subtle risk to consider with leverage is path-dependency risk, which deals with the details of different types of leverage.

At this point in the article, readers might still feel a bit unsure about the concept of financial leverage. Viewing leverage in the context of a common use case, however, may help to get a better sense of it.

Mortgages represent one of the most prevalent applications of leverage in the United States. The issuance of a mortgage typically involves an initial down payment on a home. A bank then provides the capital for the remaining purchase price of the property. To service the loan, the borrower is obligated to make monthly payments to the bank.

Crucially, a mortgage is not subject to daily mark-to-market valuations. Instead, its valuation is realized either upon the property’s sale or in the event of a default.

If the borrower keeps up with their payments, nothing significant happens until the house is sold or, in a worst-case scenario, the bank takes it back. Even if the house’s value drops, the borrower won’t face immediate consequences as long as the monthly payments are made.

In the event of a value depreciation, the borrower’s equity value might dip into the negative, yet foreclosure actions aren’t initiated if the mortgage is kept up. However, failure to fulfill these payments, regardless of the cause, can lead to foreclosure or a forced sale, potentially at a disadvantageous price, contingent upon the urgency.

To ensure consistent mortgage payments, the borrower must possess one or a combination of the following: adequate cash reserves, the ability to comfortably manage the monthly mortgage payments, diversified income streams, sustained employment (preferably outside the real estate sector, especially during a housing market downturn), or possess skills and experience allowing them to get a new job if necessary.

In essence, this translates to a fundamental principle: “The borrower should have diversified income potential or ample capital reserves.”

Comparing this scenario to a financial derivative like a futures contract reveals striking similarities.

If an investor decides to enter a futures contract, they must set aside an initial amount of money, like a down payment on a house, known as the initial margin requirement.

Here’s where it gets different: in a futures contract, the investor doesn’t make a direct payment. Instead, any interest costs are taken out of the profits made from the investment. For example, if the underlying security gains 5% over the life of the contract, but there’s a 2% interest cost, the investor ends up with a net profit of 3%. In other words, no explicit payments have to be made: the interest charged is implicit.

Profit and loss from futures contracts is settled daily, requiring the investor to maintain a certain amount of money in their account, known as a margin account. If the value of the contract drops significantly, the investor might need to add more money to their account to meet the requirements and keep the investment going. This is slightly different from mortgages where the value of the house doesn’t affect the monthly payments.

This is where path-dependency risk is introduced. Even if an investor is right in their view over the long run, if they cannot support their position in the short term, they might be forced to close the trade.

Portable Alpha and Path-Dependency Risk

Many investors learned this lesson the hard way in 2008 through portable alpha strategies. Portable alpha involves separating the alpha (active return) from the beta (market return) by using capital-efficient derivatives to maintain market exposure while allocating capital to alternative investments seeking uncorrelated returns.

For example, an institution aiming to match the returns of a benchmark index could use futures contracts to replicate that exposure without tying up substantial capital. The freed-up capital could then be invested in hedge funds or other alternative strategies to generate additional returns (alpha) independent from market movements.

Prior to 2008, this was an appealing strategy for many institutional investors seeking to boost returns and diversify their portfolios. However, when stocks sold off in 2008 and their margin capital deteriorated, many hedge funds began to gate redemptions due to mounting losses or liquidity issues making it impossible for investors to redeem their capital to replenish their margin, forcing them to unwind positions at unfavorable prices.

The UK gilt crisis of 2022 also highlighted the path-dependency risk of concentrated leverage. Pension schemes in the UK hedge their liabilities by purchasing long-dated UK government bonds. Since outright holdings of long-term bonds are economically costly, they employ leverage and pool their assets with other pension funds. As yields spiked in September 2022, large mark-to-market losses were generated, triggering margin calls. To meet these margin calls, pension funds initially sold more gilts, triggering further losses. Furthermore, many smaller pensions implemented this trade via pooled vehicles, which were limited liability. This created a principal-agent problem, as the managers of the pools were incentivized to sell positions quickly, rather than give participants time to contribute to positions. The Chicago Fed provides a more detailed analysis of the crisis.

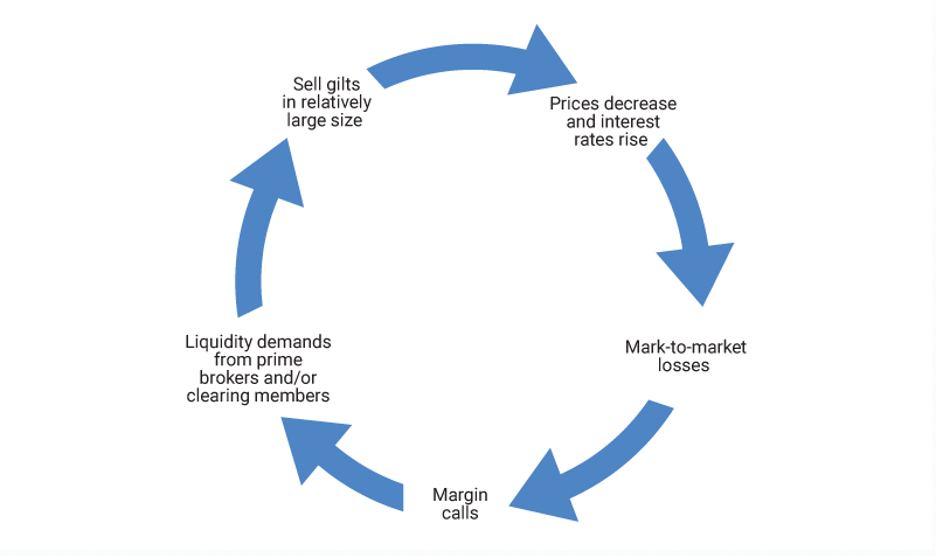

Figure 1: The Run Dynamic in UK Pension Funds

Figure 1 illustrates the downward spiral experienced by UK pension funds during the 2022 gilt crisis, highlighting path-dependency risk similar to that encountered in portable alpha strategies. It depicts a cyclical process starting with margin calls, leading to the selling of gilts in large quantities. This selling pressure further decreased gilt prices and increased interest rates, resulting in mark-to-market losses for the pension funds. These losses, in turn, triggered more margin calls from prime brokers and clearing members, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of selling, price declines, and losses.

Source: The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/chicago-fed-letter/2023/480

In both events, leverage was at the scene of the crime. However, it was leverage and illiquidity or leverage and concentration that caused the problems to spiral.

Investors in futures contracts, therefore, need to have enough cash or other liquid investments that can be quickly turned into cash. This way, they can transfer money to their brokers or sell profitable investments to support their accounts.

The Return Stacking landscape is ever evolving, go deeper by connecting with a team member.

Summarizing Leverage Risks and Potential Solutions

In the previous sections, we explored two primary risks of using leverage: Performance Risk and Path-Dependency Risk.

Performance Risk:

- Performance risk is simply the risk that returns are negatively impacted by using leverage.

- To mitigate this risk, we can properly size what we are stacking for our risk tolerances or stack diversifying exposures. By doing so, negative impacts are lessened by thoughtfully sizing or stacking an exposure that is likely to zig when our core portfolio zags.

Path-Dependency Risk:

- Path-dependency risk is the risk that an investor is knocked out of their positions due to adverse events. In financial leverage, this typically takes the form of a margin call that the investor can’t satisfy, leading to the position being liquidated.

- To contrast financial leverage with a mortgage, mortgages are typically only liquidated when the monthly payments are not met or the house is sold.

- Financial leverage is typically marked-to-market daily; therefore, to reduce the impact of such a risk, it is crucial that the assets being stacked are liquid. Additionally, by rebalancing the positions daily, the margins can be maintained daily.

Managing Leverage Risk in Strategy and Portfolio Design

We believe the benefits of leverage can be unlocked so long as we thoughtfully consider the risks we’ve outlined in our portfolio design.

- Ample Cash Reserves: Managers of levered strategies will want to ensure that they maintain ample cash reserves to meet margin requirements. Managers should consider not only normal market environments but also a variety of extreme cases, developing a plan for how further margin capital can be made available if necessary.

- Matching Liquidity: In the scenario where a levered position loses money and consumes its margin capital, other positions in the portfolio will need to be sold to free up capital. Consider the portable alpha example we gave above: turmoil occurred because allocators were not able to sell illiquid hedge fund positions to free up capital. This might sound bad, but it is no different than the considerations we’d have when rebalancing any portfolio. In an unlevered portfolio, if stocks fell faster than illiquid hedge fund holdings, an allocator would still have trouble rebalancing back to their target strategic allocation. Leverage accentuates this risk. Therefore, investors who implement levered strategies will want to consider how they will rebalance their portfolio in times of stress. Ideally, investors will also match the appropriate type of leverage with liquidity. Leverage that is marked-to-market daily—like futures contracts—is appropriate with a sufficiently liquid portfolio. For a highly illiquid portfolio—like real estate—leverage through a structure like a mortgage may be more prudent.

- Diversifying Return Streams: Leverage accentuates the risks of portfolio concentration. Therefore, investors will want to be thoughtful as to the return streams they incorporate in their portfolio. By selecting diversifying return streams, investors can better manage performance-related risks. For example, adding more equity to a 60/40 portfolio would have, historically, contributed to further drawdowns in the dotcom bust, the great financial crisis and the COVID crash. Adding managed futures, however, would have historically reduced drawdowns in all three of those environments.

- Sizing: A return stream that appears diversifying during normal market environments may become perfectly correlated with other holdings during periods of market tumult. In this case, the amount of leverage we use becomes the ultimate determinant of portfolio stress. By considering worst-case scenarios, investors can better choose a position size that significantly reduces the risk of permanent capital impairment.

Many of the risks that may emerge from the use of leverage can be addressed when it is utilized to add uncorrelated and complementary sources of return, is amply collateralized with cash reserves, and pairs similarly liquid assets.

Conclusion

In the world of investment management, leverage is often viewed with suspicion if not outright derision. Yet leverage is a potent tool. The art of utilizing leverage requires a thorough understanding of its benefits and risks.

Historically, leverage has frequently been entangled in economic crises, yet exceptions highlight its potential to benefit investors. Bridgewater Associates’ strategic use of leverage, particularly in their “All Weather” portfolio, serves as an excellent example. By intelligently diversifying across assets with varying economic sensitivities, they showcase the power of prudent leverage for enhancing staying power and potential returns.

Delving into the risks, two primary issues arise: performance risk and path-dependency risk. The former demands thoughtful decision-making, emphasizing the importance of intelligent stacking rather than haphazard accumulation. Prudent investment selection and sizing, especially in diversifying or negatively correlated exposures, are key to mitigating this risk.

The latter, embodied in daily mark-to-market evaluations, underlines the importance of liquidity and active margin management. Efficient vehicles and diversification become highly important when collateral may need to be drawn quickly.

Drawing a comparison with mortgages, a common form of leverage, reveals fundamental similarities. Both entail initial “down payments,” with the distinction lying in how the loans are serviced. Mortgages, not subject to daily evaluations, in essence mirror the leverage achieved through futures contracts.

While financial leverage is often viewed negatively, leverage is not uncommon. As with any financial decision, strategies like portable alpha, when executed thoughtfully, demonstrate how leverage can be utilized to enhance returns and diversification. By understanding and managing the risks involved, investors can leverage these strategies effectively to build more resilient portfolios.

For investors interested in exploring these concepts further, understanding portable alpha and its applications can provide valuable insights into building more resilient portfolios. As with any financial decision, careful consideration and risk management are essential in leveraging these strategies effectively.